16 Aug 2011

A recent Rasmussen U.S.

poll found that 69 per cent of 1,000 respondents believed it at least “somewhat likely” that climate scientists had falsified their research data to support the case for catastrophic human-caused global warming (CAGW). A full 40 per cent of respondents said falsification of research data was “very likely.” Only 22 per cent were confident that climate scientists

wouldn’t falsify data.(2)

This is an astonishing poll result. Is it possible that, in their passion for the CAGW hypothesis, prominent climate scientists would knowingly fudge their data to mislead the public? Surely the 69 per cent in the Rasmussen poll were innocent dupes of what global-warming activists call the “denial industry.”

Unhappily, as I discovered during more than two years of research for my book False Alarm: Global Warming—Facts Versus Fears, the 69 per cent have got it right. Over the past decade alarmist climate scientists—including the top figures in the field—have been deliberately misleading the public on many climate issues. One might even say alarmist climate scientists have developed a culture of deception, a culture that is very clear in the “Climategate” emails.

Blatant dishonesty

Among many deceptions—too many to deal with here—one is particularly blatant. For more than a decade, the public has been bombarded by claims that the planet was not just warming but experiencing “accelerated”, “unequivocal,” “unprecedented” and “dangerous” warming. Yet the actual temperature record shows that during the past decade, on average, there has been little or no warming.

Only recently, faced with a gap between the climate reality and alarmist theory that was too great to ignore, has official climate science begun to admit the facts to the public.

And so, in June, the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published a peer-reviewed article that began: “Data for global surface temperature indicate little warming between 1998 and 2008. Furthermore, global surface temperature declines 0.2 °C between 2005 and 2008.”(3) (As we will see below, the cooling trend has continued past 2008 despite a warm, El Nino-influenced 2010.)

Early in August, a press release from the British Meteorological Office admitted there had been no warming—the Met delicately called it “a pause in the warming”—in the upper 700 metres of the world’s oceans since, get this, 2003.(4) Yet, for the past eight years, the Met has warned the public about a dangerous heating up of the oceans.

One more example: A recent paper in

Science found that 5,000 years ago, at the end of the Holocene Optimum warming, there was 50 per cent less Arctic ice than today.(5) Somehow, the planet and polar bears survived. And yet, official climatology tells the public that today’s Arctic melting is “unprecedented” and that polar bears—despite the largest populations ever recorded—are endangered (for details, click

here).

No warming for a more than a decade

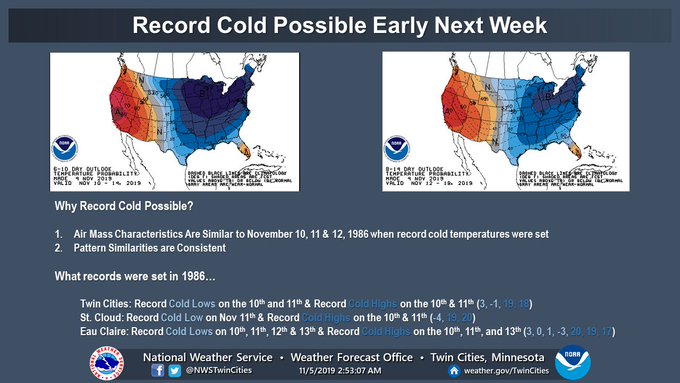

What is the climate truth for the past decade and more? Figure 1 shows the temperature data from the four major climate monitoring agencies from 1998, when warming began to slow down, to 2011.(6)

Figure 1: Temperature trend 1998-2011. Source: woodfortrees.org

Only one—the U.S.’s Goddard Institute of Space Studies (gistemp)—shows appreciable warming, about 0.175°C for this period. But, then, GISS is known for “adjusting” its temperature data upward to support the extreme warming claims of its director, James Hansen (see

GISS: Rewriting history for a better future).

Of the other three, the British Hadley Climate Centre (Hadcrut) shows no average warming at all for 1998-2011; the University of Alabama at Huntsville (UAH) shows a small .05°C of warming; Remote Sensing Systems (RSS) has the planet cooling slightly (about .02°C). Overall: if there is warming, it is slight, and far short of the 0.2°C-0.45°C/decade predicted by the 2007 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Decade ends with cooling trend

Furthermore, both GISS and Hadley tip toward

cooling as the decade progressed (Figure 2 shows the temperature record from 2005-2011), while UAH and RSS are basically flat. And some climate scientists even predict the cooling could continue for decades (for one cooling prediction, click

here).

Figure 2: Temperature trend 2005-2011. Source: woodfortrees.org

Keeping the public scared about warming

But over the decade, while the planet stopped warming and even tipped toward cooling, what did the public hear, usually through the mass media, from the alarmist climate agencies and the IPCC?

The 2007 IPCC report warned: “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal as is now evident from increases in global average air and ocean temperatures.”(7) [emphasis added] These increases, the IPCC writers must have known at the time, were not “unequivocal”—by 2007 they were non-existent.

The head of the IPCC, Rajendra Pachauri, told an Australian audience in 2008: “We’re at a stage where warming is taking place at a much faster rate [than before].”(8) [emphasis added] Yet, by 2008, surely the director of the IPCC must have known the trend was toward cooling.

Vicky Pope, a spokesperson for the Hadley Centre, said in February 2010, “If anything, the world is warming even more quickly than we had thought.”(9) [emphasis added] However, in November, a mere nine months later, Pope told reporters the complete opposite: “There’s a very clear warming trend but it’s not as rapid as it was before.”(10) [emphasis added]

University of Victoria climate computer modeler Andrew Weaver simply ignores the air and ocean temperature data in telling a Victoria magazine interviewer this summer: “The allegation that annual global mean temperatures stopped increasing during the past decade has no basis in reality.”(11)

Keeping the hypothesis alive

Yet, even though the truth is now being made public, alarmist climate science is still trying desperately to keep the CAGW hypothesis alive. For example, alarmists claim that even if the air and oceans aren’t warming as predicted, the warming is only being “masked,” or that we are just experiencing a “plateau” or a “pause” in warming—this often at the same time as they have asserted that warming was “accelerating.”

If the warming is “accelerating,” even though there’s no acceleration in the air or temperature record, where is the warming going? Some say warming has migrated to the deeper ocean levels and is just waiting to leap out at us when the “pause” ends. Therefore, they say, we shouldn’t pay too much attention to the non-warming surface and ocean temperature records. In saying this, alarmists want to have their cake and eat it too: they readily cite the air and ocean temperature record when the record shows warming, and want us to ignore it when it doesn’t. That said, so far there is no evidence that the deeper oceans are taking up the excess heat, a lack of evidence that Kevin Trenberth called a “travesty” in one of his Climategate emails.

And the alarmists dismiss out of hand the suggestion, in a

paper by Roy Spencer and William Braswell, that the excess heat is simply radiating out to space. This hypothesis makes sense if the atmospheric band that traps carbon dioxide warmth is saturated, which it almost certainly is.

Hiding the truth

By the middle of the last decade, and almost certainly several years earlier, climate scientists like Phil Jones, the head of East Anglia University’s Climatic Research Unit (CRU), knew the planet wasn’t warming the way the models said it should. They were then faced with a dilemma: tell the public the truth, with the risk that lay people would lose faith in the CAGW hypothesis; or, to preserve that faith as long as possible, keep this information within the scientific community in hopes the planet would start warming again.

In one of his “Climategate” emails dated July 5, 2005, Jones was quite explicit about his decision to withhold the truth from the public: “The scientific community would come down on me in no uncertain terms if I said the world had cooled from 1998. OK it has but it is only seven years of data and it isn’t statistically significant.” This email raises two questions: first, why wouldn’t an ethical scientist reveal that the world had cooled, if that was what the evidence showed? And second, why would other scientists object if that’s what the data showed?

In the same email, Jones wrote: “If anything, I would like to see the climate change happen, so the science could be proved right, regardless of the consequences.” In other words, if climate science could just keep the public in the dark a bit longer—if they could just, in Jones’s signature phrase, “hide the decline” long enough(12)— the climate would surely start to warm again and the CAGW hypothesis would be vindicated.

Of course, it’s not scientifically unethical to prefer a particular hypothesis, even if the empirical evidence isn’t there to support it. Alfred Wegener believed the continents moved, but it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that geological evidence proved him right. It’s possible, in other words, that the catastrophe theorists are correct even though the evidence is currently against them.

A failure of scientific ethics

But here’s the bottom line: It is not ethical—it violates all the principles of scientific honesty—to withhold from the public evidence that doesn’t support the hypothesis to avoid creating “doubt.” We expect some shading of the truth from professions like the law or politics, but scientists have a sacred obligation to report the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

In this vein, GISS’s James Hansen has written, “In order for a democracy to function well, the public needs to be honestly informed.” And, similarly, physicist Richard Feynman, wrote:

You should not fool the layman when you’re talking as a scientist. … I’m talking about a specific, extra type of integrity that is … bending over backwards to show how you are maybe wrong, that you ought to have when acting as a scientist. And this is our responsibility as scientists, certainly to other scientists, and I think to laymen.(13)

Unfortunately for the credibility of climate science, alarmist scientists did not show that “specific, extra type of integrity” over the past decade.

It would be nice to believe that most—certainly not all!—climate scientists are honest and would not deliberately mislead the public. Perhaps this failure of honesty and integrity occurred because, as biologist Peter Medawar wrote of Teilhard de Chardin, before climate scientists deceived the public, they had taken great pains to deceive themselves. Or perhaps they believed the end justified a dishonest means.

Whatever their reasons, many if not most leading alarmist scientists, like Jones, preferred the approach made notorious by the late Stephen Schneider to get public support: “We have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified, dramatic statements, and make little mention of any doubts we might have.”(14)

And so, over the decade, alarmist climate scientists tried to fool the public by stonewalling (“it’s the warmest decade on record,” which doesn’t mean the decade was warming), denying the facts (“the allegation that annual global mean temperatures stopped increasing during the past decade has no basis in reality”), or outright lying (“the world is warming even more quickly than we had thought”).

What we now know

It’s difficult for non-scientists to assess the truth or falsehood of scientific claims. However, with enough evidence, we can assess in hindsight whether what we were told was accurate and truthful, or not.

As the Rasmussen poll shows, and particularly thanks to the Climategate emails, a growing majority of the public is now fairly certain that alarmist climate scientists falsified or distorted research data to support the CAGW hypothesis (which they did, e.g., Keith Briffa, from the Climategate emails: “I tried hard to balance the needs of the science and the IPCC, which were not always the same”(15)).

The public can be completely certain that many leading alarmist climate scientists deliberately distorted the facts in communicating with the public over the decade (e.g., “accelerated” warming when there was none). And this failure to be honest with the public about the past decade’s non-warming is only the tip of a very large iceberg of deceptions, including the claim that climate science is “settled” and “certain.”

The climate will eventually warm again—“stable” climate is an alarmist myth—and alarmist climate scientists will no doubt beat their doomsday drums even harder, while continuing to exaggerate the facts in what they tell the public to win support for the CAGW hypothesis. But after a decade of deception, who will believe them in the future? Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.

Sources and Notes

1. James E. Hansen, Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth about the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our last Chance to Save Humanity. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009, p. 112.

2. Rasmussen Reports, “69% Say It’s Likely Scientists Have Falsified Global Warming Research.” August 03, 2011.

3. Robert K. Kaufmann, at al., “Reconciling anthropogenic climate change with observed temperature 1998–2008.” PNAS, June 2, 2011.

4. “Pause in upper ocean warming explained,” British Meteorological Office, Aug. 4, 2011.

5. Svend Funder, et al., “A 10,000-Year Record of Arctic Ocean Sea-Ice Variability—View from the Beach.” Science, Aug. 5, 2011, pp. 747-750.

6. This data is available though the woodfortrees.org website, which puts the climate temperature data into graph format. NOAA also has a gadget that allows browsers to check temperature trends for the continental United States: the URL is http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/research/cag3/na.html. For 1998-2011, the NOAA site shows major cooling of 0.5°C.

7. IPCC 2007 Summary for Policymakers, p. 5.

8. Michael Duffy, “Truly inconvenient truths about climate change being ignored.” Sydney Morning Herald, Nov. 8, 2008.

9. Jonathan Leake, “World may not be warming, say scientists.” Times Online, Feb. 14, 2010.

10. Alex Morales, “World May Post Warmest Year as U.K. Met Office Adjusts Past Decade of Data.” Bloomberg, Nov. 26, 2010.

11. Amy Reiswig, “Tunnelling through the Wall of Hate.” Focus, July/August 2011, pp. 34-35.

12. Jones was referring to the cooling shown by tree ring proxies after the 1960s, rather than the surface temperature record. Nonetheless, “hide the decline” is the right term for official climate science over the past decade.

13. Richard P. Feynman, “Cargo cult science: The 1974 Caltech Commencement Address,” in The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman. Cambridge, MA: Persius Books, 1999, p. 212.

14. Schneider is quoted in Jonathan Schell, “Our Fragile Earth.” Discover, October, 1989, pp. 45-48. See also Stephen Schneider, “Don’t Bet All Environmental Changes Will Be Beneficial,” APS (American Physical Society) News, August/September 1996, p. 5.

15. Keith Briffa email to Michael Mann, April 29, 2007.

,

,